Improving the usefulness of the five years of our life we spend dreaming and the fifteen or so years we spend in deep sleep is a smart thing to do, because learning to be fully alive in the here and now, moment-to-moment, is a wise way to live. As increasing numbers of people learn about lucid dreaming and dream yogas, as we continue to increase our ability to network and gain wider access to both historical and contemporary related approaches in the scientific, social, cultural, and subjective quadrants of human exploration, we will more quickly recognize our own beliefs and expectations about dream yoga to be both conditioned and antiquated. Next year, in 2020, in the context of an extremely broad-based psychotherapy practice in out-patient, in-patient, and private practice settings, I will have spent forty years of my life interviewing dream characters and the personifications of life issues. While I have certainly learned some things about truth and reality, what this practice has most centrally taught me is humility – to recognize the limitations of my waking perspective and to consider my conclusions, including those which I am writing here today, as tentative and subject to multiple changing factors.

I have moved toward greater humility not by choice or nature, but as the inevitable outcome of the type of dream yoga which I practice and teach in my certification programs. Because it is fundamentally phenomenological, Integral Deep Listening (IDL) dream yoga sets aside a broad assortment of common assumptions in favor of taking the perspective of this or that dream character or personification of a life issue, collectively called “emerging potentials,” and practicing listening to them in a deep and integral way. Because IDL is multi-perspectival, it is endlessly creative and transformative. Because IDL involves embodying other perspectives, it intrinsically involves disidentification with one’s waking identity or any ego, self, Self, Atman or anatman. This both thins and de-centralizes our sense of self, so that it is objectified, as if it were a hand or a tool, something we highly value and use for growth, but which does not define our reality. The consequence of such a practice is that our prized interpretations, assumptions, and preferences are tested against those of multiple emerging potentials. Because they are consistently found limited, partial, or flat out mistaken, humility is the inevitable result.

This is not the sort of ingratiating humility of my southern roots or the socially appropriate humility of a Confucian-style ethic, but more of a Socratic recognition that one knows that they don’t know. This is not a philosophical agnosticism, skepticism, or nihilism, but much more a phenomenological suspension of the assumption that one knows, without thereby picking up some positive position about the value of unknowing, which would be a luddite position, a short-sighted dead end.

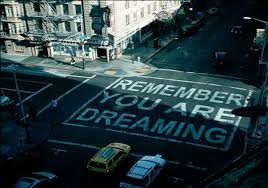

Becoming lucid is a comparative practice and assessment. While we think we are “awake” or even “enlightened,” in reality, we have awakened into a broader state of subjectivity. For example, if you wake up in a dream you may feel exhilaration, freedom, power, and control. However, who has awakened? Your waking sense of who you are is who and what is lucid. Therefore, your lucidity is conditioned by the framing of your waking sense of who you are – your scripting, your cultural conditioning, your unconscious assumptions, logical fallacies, cognitive distortions, cognitive biases, waking preferences, assumptions, and world view. You are still asleep within your waking identity; you are simply aware that you are dreaming, and therefore can exercise greater choice and therefore control within the dream state.

The logical conclusion of this line of thinking is that we need to make the most out of accepting and enhancing our typical subjective state of awareness, of our normal, waking sense of who we are. We need to wake up out of that. But while lucid dreaming provides a powerful metaphor for doing so, one does not necessarily lead to the other. We can easily conclude that because we are awake, enlightened, and have some superior window not simply on truth, reality, and the path to personal fulfillment, but on Truth, Reality, and Nirvana, the Way, Tao, Heaven, and Enlightenment. In our own minds, we can move from an experience of conditioned to absolute reality, from an experience of relative truth to absolute truth. Because we fear uncertainty and loss of control, these are extremely enticing conclusions. We may not only believe we know Reality and Truth for ourselves, when we have probably simply expanded our delusional context, but now we can believe we have found the universal Reality and Truth and begin converting others to our enlightened vision. The problem with such an approach is that it is quite presumptious. Is my truth your truth? Is my path your path? Is there truly a universal path? Do I know that or is that my belief, based on my own personal experience?

We can do quite a bit in a dream without being lucid, that is, aware while in a dream that we are dreaming. In fact, the desire to wake up in a dream may hide or avoid the challenge of becoming more awake in the decisions we make in regular dreams, that is, when we are not aware that we are dreaming. The value of focusing on non-lucid awakening is that transformation largely happens when we are in subjective states of oblivion, not in those rare moments of clarity, whether awake or asleep. We learned to walk and talk in such states; we largely sleepwalked our way through school; most of the work we do and the relationships we maintain occur within a context of scripted sleepwalking and dreaming.

Examples of waking up, or “non-lucid lucidity” one can practice in normal dreams include choices to enter or avoid the Drama Triangle – the three roles of Victim, Rescuer, and Persecutor; asking questions of other dream characters, whether allies, antagonists, or neutral objects, like cars and trees; becoming other dream characters and perceiving reality from their perspective instead of yours; meditation; helping others, particularly those outside our waking circle of empathic outreach; and generally practicing listening to our dream experience while dreaming in a deep and integral way. Emphasizing what we can do in a non-lucid state is not meant to imply passivity or only receptivity, as listening often does. Instead, it is about learning to deeply listen while acting, taking risks, extending ourselves, even while we are asleep and oblivious to the fact that we are dreaming.

One of the advantages of interviewing emerging potentials, both awake and while dreaming, is that they can provide immediate access to states typically only accessible through drugs, near death experiences, or years of meditation. This is because interviewed dream characters and the personifications of life issues, never having been born in a physical sense, cannot die. Therefore, for the most part, they do not express perspectives that fear death. In addition, interviewed emerging potentials are not conditioned by time, space, or our personal script. They have their own perspective which is privy to our own, to the extent that they are aspects of ourselves, but those perspectives also, at the same time, transcend who we are. Interviewed emerging perspectives include our own perspective and then add their own on top of that. As a result, these interviewed perspectives typically dwell in one or another transpersonal dimension. That is, beneath their recognizable and easily categorized facade, they either manifest a sense of oneness that is energic, or one with nature, devotional, formless, or non-dual. Because we can return to these perspectives any time we like, or discover new presentations of each, IDL interviewing takes the mysticism out of the transpersonal and makes the secular sacred by finding and experiencing emptiness in bottle tops, plastic waste, chewing gum, and spit, among other things.

In her blog post, Psychospiritual disciplines of lucid sleep, Kimberly Mascaro writes, “In her 2017 book, Yoga Nidra: The Art of Transformational Sleep, Desai points to the research demonstrating the increased delta activity, which is ‘associated with empathy, compassion, intuition and spirituality,’ among experienced meditators and even monks.” Claims of higher moral development (greater empathy, compassion, spirituality) among adepts require validation. I have observed that ascended masters, non-dual meditating Zen monks, and Dzogchen-practicing Tibetan monks can be as immoral as anyone else. Ken Wilber, who has demonstrated the ability to access Delta at will while hooked up to EEG, (1) is no more moral than say, your average “deplorable,” although he is both much smarter and has had multiple, varied mystical experiences as an advanced meditator. While we may have ample evidence of the ability to lucid dream or enter Delta, deep sleep awareness at will, that does not necessarily imply advances in empathy, compassion, or spirituality. Where is the evidence that people who attain these states are more empathetic, champion universal human rights, or fight for justice more than those who have no experience in any of these areas? As Hitchen’s Razor states, “What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence.” I will go a step further and say such claims should be dismissed without evidence, because those who claim extraordinary competence require extraordinary validation and require being held to higher, not lower, standards of transparency and accountability. We can easily have too much “gee whiz” hopey, warm and fuzzy freezing up of our frontal lobe dendrites around both lucid dreaming and nidra yoga.

This observation is about as popular as a skunk at a picnic with those who are interested in dream yoga, like I am, but realism is not the enemy of idealism. Rather, it is the grounding or foundation in which any authentic development must be rooted. Otherwise, we set ourselves up for disappointment and disillusion when an oversold practice turns out to be more difficult or deliver less than promised. Then we are usually faced with the reason being our lack of discipline, focus, not saying “om” correctly, not focusing on our breath in the right way, or long enough, or whatever. It takes some time for most students to wake up and ask the question, “What if the problem is not my practice; what if the problem is that the method just doesn’t live up to its claims?” For example, we now have millions of meditators around the world using a vast variety of methods. Where are all the promised siddhis? Certainly out of all those practitioners we should have some genuine levitators by now or people who show other extraordinary competencies that are not due to physiological training, like Tummo or slowing heart rate, which can be done independently of meditation and spiritual practices.

Mascaro also writes, “The point of sleep yoga is to train oneself to access such states consciously so as to bring them back to waking consciousness!” I totally agree; however, there is a wide range of opinion about just what is being brought back to waking consciousness by these practices. The sorts of questions realism asks about such a statement include, “What correlation, if any, does bringing such states back into waking consciousness have to do with getting out of the Drama Triangle in the three realms of waking, thinking, and dreaming?” Are practitioners intrinsically less in the roles of Victim, Rescuer, and Persecutor? (I have written a book about this, Escaping the Drama Triangle in the Three Realms: Relationships, Thinking, Dreaming.) “What correlation, if any, does bringing such states back into waking consciousness have to do with increased empathy, as determined by out-group members, that is, those who do not hold our world view but are nonetheless affected by our world view and our actions?” Such questions are meant to remind us that authentic change involves all four quadrants of the human holon – not just interior intent or consciousness, but our values, behaviors, and relationships.

Arriving at a realistic approach to dream yogas, despite being a strong advocate for them, comes from a desire to protect others from both their own idealism and their desire to compensate for their own inadequacies by throwing themselves into fascinating esoteric practices. That is what I did for years, and I would like others to have the benefit of learning from my mistakes. I am also on guard regarding gurus and adepts who make unsubstantiated claims, collect disciples, and then proceed to abuse them. Adherents can easily get caught in guru-chela relationships that are not unlike those of abused spouses who keep going back to dysfunctional relationships. I cannot keep people from doing so, but at least I can attempt to provide them with an alternative framing to access when and if they experience abuse. In addition, I want to remind everyone that waking up out of everyday drama, misperceptions, delusions, and scripting, is far more important than waking up in other states of consciousness, and that while there are indeed knock-on effects of waking up while dreaming or deeply asleep, the shortest, most direct route to enlightenment, is to learn to live our waking lives with authenticity, honesty, trustworthiness, power, and empathy. This not only wakes and lifts us up; it helps others to do the same. Those waking changes can positively affect both dreaming and deep sleep.

The good news is that we really can wake up. Like enlightenment, waking up is not a goal or a state, but a process, something that never ends. We can be more awake, and we know we are because we don’t keep making the same mistakes; we look for fewer activities and people to rescue us from boredom problematic relationships, or our own self-criticism. We can be more creative and focus on solutions rather than problems, and on helping people where they feel they are stuck, rather than where we think they are stuck. IDL has a process to validate this claim for waking up, called “triangulation.” It tests our beliefs of change with three different sources, our common sense, the feedback of experts, and interviewed emerging potentials. When these three different points of view agree, we are much more likely to really be effective or awake than if just one or two of them agree. (Triangulation is explained here: https://www.integraldeeplistening.com/triangulation-a-superior-approach-to-problem-solving/)

Dreaming and deep sleep are indeed our most misunderstood and under-utilized innate resources. When we learn to wake up within these states and integrate them with our waking sense of who we are, mankind will take a major leap in its development.

For more information about the overall framing of IDL as a practice, see Waking Up. For information about IDL dream yoga certification programs, see IntegralDeepListening.Com.

(1) “….At some point in the evening we got into a discussion about meditation and the changes it can produce in brain waves. A young man training to be a psychiatrist asked me to get out a videotape I have of me connected to an EEG machine while I meditate he believed none of the discussion about how meditation could profoundly alter brain waves, and he wanted ‘proof.’

The tape shows me hooked to an EEG machine; this machine shows alpha, beta, theta, and delta waves in both left and right hemispheres. Alpha is associated with awake but relaxed awareness; beta with intense and analytic thinking, theta is normally produced only in the dream state, and sometimes instates of intense creativity; and delta is normally produced only in deep dreamless sleep. So alpha and beta are associated with the gross realm; theta with the subtle realm; and delta with the causal realm. Or, we could say, alpha and beta tend to be indicative of ego states, and delta of spirit states. Delta presumably has something to do with the pure Witness, which most people experience only in deep dreamless sleep.

This video starts with me hooked up to the machine; I am in normal waking consciousness, so you can see a lot of alpha and beta activity in both hemispheres. But you can also see a large amount of delta waves; in both hemispheres the delta indicators are at maximum, presumably because of constant stable witnessing. I then attempt to go into a type of nirvikalpa smadhi — or complete mental cessation — and within four or five seconds, all of the machine’s indicators go completely to zero. It looks like whoever this is, is totally brain-dead. There is no alpha, no beta, no theta–but there is still maximum delta.

After several minutes of this, I start doing a type of mantra visualization technique — yidam mediation, which I have always maintained is predominantly a subtle-level practice–and sure enough, large amounts of theta waves immediately show up on the machine, along with maximum delta. The fact that theta, which normally occurs only in dreaming, and delta, which normally occurs only in deep sleep, are both being produced in a wide-awake subject tends to indicate a type of simultaneous presence of gross, subtle, and causal states (e.g., turiyatita). It is, in any event, attention-grabbing.”

One Taste, Ken Wilber, pp, 75-76